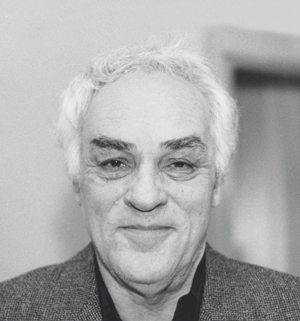

I recently came across an old tape recording of two excerpts played by violinist Gerald Beal and was again impressed by his exceptional artistry. I first met Jerry during a tour with the Royal Ballet on which he was assistant concertmaster and I a cellist. Jerry became famous as a child prodigy and toured with his identical twin brother playing violin duos. Jerry was both an amazing character and someone who was notorious for making things up. He lived in a strange world; it was defined on one side by genius and on the other by fantasy. It is impossible for me even now to separate fact from fiction with Jerry.

He had been a long-time student of famous violin teacher Ivan Galamian, and Jerry also studied with Jascha Heifetz at a time before he gave

masterclasses. On this tour my violinist wife June asked him for a lesson on how best to practice scales. I was intrigued to learn what he might say and audited the lesson. Afterwards I jumped in with a few questions and in less than 45 minutes he permanently elevated the level of my playing beyond anything I had done before. Following this experience I studied with Jerry over the next five years and grew to appreciate his extraordinary generosity and musical genius.

At the time I began studies with Jerry, I was extremely tight while playing and found it difficult to express myself musically. One night in a hotel room in Seattle, Jerry demonstrated a series of exercises, the goal of which was playing with the least possible pressure to produce a sound. I objected vehemently and often to the very concept of not using pressure because the pressure of the bow on a string is what produces the rich sound. I endlessly declared, “You must be out of your mind.” He patiently suggested that I simply try it. I know of no other teacher who would have put up with my stubbornness. Somehow I eventually got the hang of it and realized that the concept behind pressureless playing was that this would demonstrate that every note has a beginning (the attack), a middle (the development), and an end (a tapering off or a connection to the next note). In short order Jerry opened my consciousness to the connection of silence to sound, the infinite variety of expressions within the sound, and the joining of sounds to silence. In 90 minutes Jerry organized my playing in terms of attack and release (the release part was what gave me the most problems).

I soon developed a degree of control I never imagined possible. His diligent and patient guidance made my playing good enough to win the principal cello chair with the Lyric Opera of Chicago. There were only three weeks between the end of the American Ballet theater season and the first rehearsal with the Lyric Opera. The opening opera that year was Richard Strauss’ Salome. Jerry impressed upon me that it was most important that I begin well and play it beautifully and well. We worked through the entire cello part and the important solos in the B cello part.

During those lessons we explored every note and technical difficulty. Before long I had memorized whole sections of the work. I find it difficult to explain in words the extraordinary imagination he brought to making every line of notes technically solid and musically compelling. It took about 24 hours of intensive work over three days to reach this level. As I think back about the generosity of his soul that led him to work, unasked for, to bring me up to this level, I now realize that he understood how important it was to make a stunning first impression on the conductor, general manager, and orchestra members because this would cement forever my relationship with this orchestra. With his help I played the first performance on that opening night like a concerto. I led the cello and bass sections with a level of power I have rarely experienced since then.

On two later occasions Jerry pulled me through difficult performances with his extra effort and daily lessons. This was so far above and beyond what anyone else had done or I had any right to expect. On one occasion I learned to play the Dvorák concerto; in lesson after lesson he encouraged me to pull every bit of beauty out of the music. The other was my first New York solo recital, for which he gave me daily lessons for six weeks before this transformational experience.

On some level Jerry knew that he had an unsavory reputation among musicians, and he encouraged me not to mention in print that he had been one of my teachers. To this day I cannot define who he really was. There is no doubt, however, that his generosity and patience with a most difficult student were pivotal in my career, and for this I will be forever grateful to him.