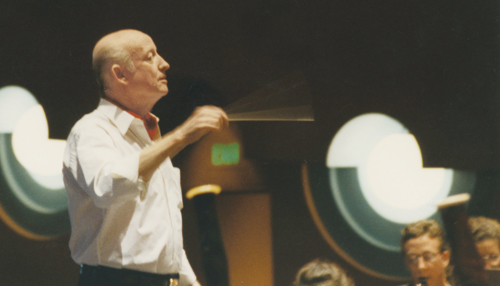

Francis McBeth was a skilled writer of both music and words. As the son of an English teacher he took justifiable pride in his usage of the King’s English and contributed a long series of articles to the pages of The Instrumentalist. Included here is the first of two installments of selected excerpts.

In the Beginning

How did you develop a passion for writing music?

I grew up in a family of good musicians. My father was taught Greek and Hebrew most of his life and was also a fair amateur horn player. My mother had degrees in music and was the church organist. In a church service the organist can choose what to play only for the offertory. So before I even started school my mother and I had a thing going between us, and I got to choose the offertory. I often chose Schumann probably because she played lots of Schumann. So, the offertories were our own little concert between my mom and me. If you hear good music before you start going to school, it never leaves you.

As a junior high student in west Texas I thought something was wrong with me because I was the only human I knew outside my family who liked jazz and serious music. When a movie came out about the life of Schumann, it was the first time in my life I had heard symphonic music other than through the scratches of the old 78s at home. The scratches were often louder than the music. In the movie, with Paul Henreid playing Schumann, Katharine Hepburn as Clara, and Robert Walker as Brahms, there was a good sound system and the music was played by a symphony orchestra. The orchestra played a lot, and I stayed through the film twice that day just to hear the orchestra. It was one of the greatest things that ever happened tome. I went back the next day just to hear that orchestra play music that I liked a third time.

I attended a Dallas Symphony rehearsal at which Antal Dorati conducted the Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique. For a fifteen year old the repertoire couldn’t have been better. I had never heard anything like that sound in my life and thought that playing in a group like that would be the greatest experience of a lifetime. When I did play in a symphony orchestra, I thought conducting would have to be the greatest experience on earth. Then when I started conducting, I thought that writing the notes for these people to play would be the ultimate experience. All three have a special happiness in them. (1998)1

The Voice of Experience

In 1961 I conducted my first high school honor band. I was 27 years old and had the confidence that youth brings, but after the first day of the clinic I was smart enough to realize that I had much to learn about how to work faster. At home I could hold sectionals with my band or talk to individuals in the hall or over a Coke at the student center about their approach to the 7th bar after rehearsal letter J. A two-day session with an honor band doesn not afford this luxury.

The most important secret of clinic work is knowing what to leave undone. I have taught theory to college students for 40 years. A large portion of all theory books deal with the rare problems of unusual harmonic usages. It takes more print to explain the exceptions or oddities than to explain a common usage. I now forgo the oddities until we have learned and perfected all the common usages.

An efficient clinician starts with what he considers the number one priority and subsequently works through the others. I believe that the first priority is interpretation. I place it above all else because of imprinting. If the technical aspects precede this, students usually learn the incorrect interpretation, and then have to unlearn this. Never allow incorrect interpretation, no matter what technique is being repaired. Even more important, when this aspect is poor or wrong, all else is to no avail. Because I have written extensively on the subject, I will only mention that tempo and volume variants are the most important elements in interpretation. I spend the first day of rehearsals working mostly with volume variances, which are not just a matter of how loud or soft, but graduating to and from them. Phrasing involves volume variances, and even a phrase ending is affected by it.

Only when I get the interpretation close to what I want, do I turn to the mechanics. Not so much now, but in earlier days, I would have directors point out that the clarinets were missing notes in the run at letter D. I would reply that I was aware of it, but there is plenty of time after we achieve the attitude to fix notes. They didn’t understand the importance of the famous quote by Beethoven, “Wrong notes are of little consequence, but to play without passion is inexcusable.” To make music is the first priority, to clean it up then follows.

* * * *

Be Careful

Some years ago in Knoxville, Tennessee I stepped into the hotel coffee shop following a concert and saw Wynton Marsalis sitting with his high school band director, Peter Dombourian. Because I knew Pete well, I thought it a great opportunity to meet this trumpet virtuoso. As I approached the table Wynton Marsalis got up, walked toward me, and called me by name. I was so surprised and asked him if we had met before. He replied that he was in the Louisiana All State Band in Shreveport when I was the guest conductor.

Some years ago in Knoxville, Tennessee I stepped into the hotel coffee shop following a concert and saw Wynton Marsalis sitting with his high school band director, Peter Dombourian. Because I knew Pete well, I thought it a great opportunity to meet this trumpet virtuoso. As I approached the table Wynton Marsalis got up, walked toward me, and called me by name. I was so surprised and asked him if we had met before. He replied that he was in the Louisiana All State Band in Shreveport when I was the guest conductor. Marsalis proceeded to list the entire program that we had played, piece by piece, and during our visit quoted many things that I had said. It was after this visit that I began to reflect on the seriousness of every comment front of an ensemble. Here was a world-class performer who remembered what I had said when he was in high school. It brought home to me that anything I say in front of an honor band had better be correct, especially the criticism, because those students will never forget it. That’s a heavy responsibility. (1997)2

Repertoire Evolution

How much has the repertoire for band changed over the past 40 years?

The big change happened in the 1950s and 1960s because everybody as mad and excited and sparks were flying. Band directors were screaming that this wasn’t music. It was a wonderful time.

The hallmark piece that brought everything to the fore was Clifton Williams’ Fanfare and Allegro because it didn’t make everybody mad and was viable music. It brought the 20th century into the brains of high school band directors, and from that point everything grew. We would not have heard the music of Persichetti in the 1960s if it weren’t for Williams. With the passing of the guard, things changed tremendously because the old guard would never accept the new literature, but the younger conductors loved it.

When Persichetti’s Pageant was played at a major state contest, some of the judges were so upset that they called him that evening. He wasn’t home but they got his hotel number in Miami from his wife and called him there. They asked if at a particular place in the piece it went “bang-crash-boom” or did it go “boom-crash-bang-thump” and then hung up. The new music made some directors extremely agitated. Even the students were excited in the sixties because they would try anything. (1998)1

The Dark Side

What music did you have in mind when you spoke of ugly music?

Some of the experimental music that we were afraid to challenge and almost all of the twelve-tone music. I am thrilled to have lived long enough to see twelve-tone music vanish. What a wonderful time, the Russians embracing Capitalism, the Berlin wall is down, and serial music has just gone away. Are these not causes for rejoicing.

The twelve-toners tried to lower music to the level of science. The dodecaphonic period lasted as long as the Classical period, and what do we have to show for it? You can count them on one hand. Alban Berg was good because he cheated. He said, “I still want to use my ears.” it was tough on students at many schools in those days; if you wanted to make an A in composition, you had to turn in a piece where in the stretto, retrograde, inversion and augmentation, every third note formed a recipe for kidney pie, and if you held the score up to an incandescent bulb, it formed the outline of Sandra Dee. Fortunately, we are trying to return to music that touches the soul instead of perplexing the brain.

* * * *

Advice to Directors

What is your approach to rehearsals?

I plan rehearsals so I know what I will end with because I don’t want the bell ringing while working with only two players on a duet while the rest of the band has sat for six minutes. This would leave a bad taste in their mouths. I want to end big with everybody participating. I have also quit working on a passage that needed more time because too many people have to sit for an extended time. I force myself to rehearse as fast as possible and limit talking to the fewest words necessary to achieve what I want. Rehearse the sections that need rehearsal; skip those that don’t.

One of my favorite stories happened to my son. After a public school concert we discussed a particular work they played, and I said the first half was excellent and the second half was terrible. How could that be? My son said, “You know Dad, the spot where it got bad is the place where the bell rang every day.” (1991)3

On Tempo

In discussing the elements of interpretation, tempo would seem to be the simplest to correct or perform right, but it is the one element that if incorrect will destroy a good work immediately. In 19th century music tempo is usually indicated by terms. In the 20th century it is more specifically denoted with actual metronome markings. How, then, can there be any mistake in tempo in a work marked by a metronome indication. Easily.

In discussing the elements of interpretation, tempo would seem to be the simplest to correct or perform right, but it is the one element that if incorrect will destroy a good work immediately. In 19th century music tempo is usually indicated by terms. In the 20th century it is more specifically denoted with actual metronome markings. How, then, can there be any mistake in tempo in a work marked by a metronome indication. Easily. First, composers very often put the wrong tempo on their music. This would seem impossible, but the tempo that seems best at the writing desk is very seldom the best on the podium. Most composers are not conductors, and the true tempo for a work can only be felt in a physical performance. Tempo is like water, it seeks its own level and this seeking only occurs in actual performance.

To avoid this problem I never publish a metronome marking until I have conducted the work at least five times in public performances. I say pubic performance because this is not always the same feel as at rehearsals.

Much band music and some orchestral tempi are chosen by the conductor solely from the gymnastics approach. At a concert last year two conductors seemed intent on showing how fast the outstanding band could play. The performance was a musical disaster by a great band solely because of tempo. I judged a tape this year in which the percussion variation in James Barnes’ Paganini Variations was impeccably performed at almost twice the tempo it should have been played. It caused this wonderful variation to sound silly.

****

On Volume

When I speak of volume variants, many think that I am talking only of playing loudly or softly. Volume variants include so many aspects of playing – articulation, the accent is a volume variant; phrasing, the phrase ending is a volume variant; the complete curve of a phrase is a volume variant, the crescendo, the decrescendo, the timpani volume, and just plain louds and softs.

The composer primarily speaks through volume variants and dissonance with melody and rhythm a distant second. I have sat many times with composers as they listen to their own works. They always mumble throughout the entire performance. The mumbling invariably goes like this:

“Too fast – louder trombones, louder – too loud trumpets – come on timpani, we can’t hear that – no, no sffzp, band, sffzp – can’t hear the tubas.” When it’s one of my works, my wife has to listen to all the mumbling.

I never hear composers mumble, “Oops the flutes are sharp – poor subdivision in the clarinets – brass balance is poor,” they always speak of tempi and volumes.

Why are volumes so difficult to sense? One seldom hears the Brahms Second performed with different volume concepts, but you surely will with Fanfare and Allegro. I have never heard a composer conduct one of his pieces without pleading for more volume from the timpanist. Most high school timpanists just can’t play at a fortissimo, and it’s so easy. The same is true for French horns.

After I have rehearsed an all-state band for two hours, I invariably hear from a player or band director, “Oh you want the horns and timpani to play real loud,” to which I reply, “No, not at all. I want the same volume at an ff from them that Hanson wants in his music or Ansermet uses in Stravinsky. I want the same timpani volume at ff that the timpanist in the Chicago Symphony uses.” It’s not a matter of skill or technique, experience, or age.

* * * *

In my work Masque (pronounced Mask by the way not Mosque) there are two measures that I have seldom heard done correctly. there are two adjacent measures in which the band has an sffzp<ff over three beats at a tempo of 156. Most bands will not get down to the p or up to the ff because it happens so fast. When I point this out in clinics, I play a tape of it being done perfectly by a high school band from Kaho, Japan. the extreme quick change of volume is so exciting. (1992)4

Inspiration and Perspiration

The world of creativity is one of fantasy, and fantasy is one of life’s greatest states, which so few of us choose to enjoy. All children live in a world of fantasy, but unfortunately most grow out of it.

Fantasy is a magnificent vehicle that transports one out of time and to a place without danger or fear. Fantasy allows a person to be all he wishes to be even if just for a moment, but it is these moments away from reality that bring such comfort and pleasure to existence. Without these flights, this earthly travail is deprived of the beauty that makes the heart soar. It is the soaring of the heart that gives the greatest pleasure and joy.

Why does a person desire the experience of hearing a great piece of music? Many don’t, but of those who do, why is it such an experience? What do we derive from it? Wagner said, “Music allows us to gaze into the innermost essence of ourselves.” I can give a list of other quotes, but they are all as hard to comprehend as the original question is to answer. I have asked many people what they receive from great art, and the usual answer is happiness or joy. I am not sure.

I experience happinesss and joy in many ways, especially from my children, but this is a different emotion than I receive from the Shostakovich Tenth or Andrew Wyeth’s Helga paintings. It is different from just happiness or joy, it is a feeling that I know no words that can accurately describe it.

When I experience great art, it seems to expand my lungs and change the chemistry in my physical body. It releases the ultimate sensation of contentment coupled with exhilaration. There is nothing in our lives outside of religion that quite equals this mental and physical state.

If this is true, and it is in my case, why do the majority of people not seek it out? The answer is one that I will never discover. It will always be one of life’s greatest mysteries, so I will not pursue it further.

If to experience this gift of art is so grand, to create the experience is a state that is even more beyond description. If the passive recipient of art is so affected, just triple, quadruple, quintuple it for the active participant in its creation. In music the performer is exalted to a higher plane, the conductor to an even higher, and the composer to the highest. The creation of art may be the highest level of personal satisfaction that is achievable. I have never found any other endeavor that supersedes it.

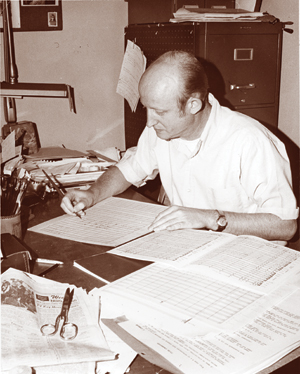

The act of creation is not in itself a particularly grand experience. That comes after the fact. The act itself is very hard and frustrating work. Many first year composition students struggling with this frustration have said to me, “This is not as much fun as I thought it would be.” I reply that hard frustrating work is never fun. The pleasure comes after th work is finished. Everyone wishes to be able to play, but only a few will practice. Everyone wishes to have written, but few want to write. Creative work is difficult, frustrating, and laborious.

In all creative arts the process of composing music is the least understood. The basic process of writing plays, of painting, of sculpture is comprehended by most of the public; but the ability to put sounds on paper that creates music is a mystery to most people. To write a simple song is more or less understandable, but composition beyond that is considered magical to the layman. to put colors on a white surface has been done by almost all people; to write words on paper, the same; but to organize sound in a logical manner is very foreign to the general population. (1994)5

The Art of Programming

A pre-clinic priority is choosing the program and its order. I am often puzzled why some programs and their order have been chosen. I have always liked Harold Bachman’s programming advice, which was that when you thought you had settled on the perfect program, you could always make it a degree better by cutting one number.

When Howard Dunn, who I considered one of the top music educators in America, took a course in programming from a very famous American orchestra conductor, one of his assignments was to turn in a sample program. This teacher remarked that he could tell that Howard had never conducted for money. Howard asked what this mean, and the teacher said, “You are ending the concert with Strauss’s Don Juan.” Howard answered by saying that Don Juan was a great masterpiece. His teacher agreed, but said, “that has nothing to do with the problem. The problem is that you will be leaving the audience and your season ticket holders for the evening with a pianissimo pizzicato in the strings.” His point was not about the quality of the music but the placement. A program should not be a potpourri of compositions the conductor likes, but a dramatic progression to somewhere. A program should be constructed just as a composer plans a composition. The chosen works must complement each other as foods do at a good meal.

I have had many young people tell me that they planned to major in music education until they played under a particular director in an all-state ensemble. There are so many horror stories from the 1940s and 1950s, and they always depress me.

A good clinician must have great patience and do anything to help the students while treating them with respect and kindness. There is a time when harsh words are appropriate, as when dealing with unacceptable behavior or bad attitudes. Poor behavior or bad rehearsal discipline is usually not the students’ fault but reflects the norm for behavior at their schools during band rehearsals. They are usually surprised when you won’t accept it. This can always be handled with firmness on your part and without meanness.

Bad attitude is something else. It deserves harsh words, and I will give them. I will not overlook a bad attitude and may overreact to it, but that’s my problem. In 40 years of teaching I have encountered it seven times, four in freshman theory classes and three in all-state bands. I can vividly remember each case, and I immediately threatened expulsion from the class or band. I will not stand for bad attitudes; there is no excuse for it. There will be times, though few, when a bloodletting is not only appropriate but mandatory for bad attitude. (1997)2

On All-State Bands

Today the goal of all-state bands is to bring in an exceptional musician and conductor who can give the group a once-in-a-lifetime musical experience. This is done through the choice of literature and the conductor’s ability to communicate the musical interpretation of the literature. A few conductors are only concerned with precision of rhythm and pitch. Good rhythm and pitch are techniques that must be attained, but technical precision does not make music. Technique is the frame to which musical expression is attached. Some high school directors rehearse with a loud metronome because they think the tempo must stay strictly the same. This is in direct opposition to the way that musicality and interpretation are achieved. Music does not stay at a set tempo unless it is a very specialized piece, like a march. For good musicality and expression the music must move ahead a little and slow a bit where needed. The places that these occur are determined by the musicality of the conductor because they are not marked. If they were indicated, they would be overdone. They must be felt.

The greatest change that I have witnessed over 50 years is the huge advancement in the level of playing, which has opened the door to performing excellent literature. It has also encouraged the new generation of composers to look to bands as an artistic medium that would support their work. I recall a piece that several all-state bands played in the 1950s that is now performed by good junior high bands.

There has also been a great change in the students. They have changed in attitude, dress, and discipline. It is much harder to get good rehearsal discipline today, and the beginning of the first rehearsal is spent getting boys to remove their caps. I have found that sloppy dress and the wearing of caps contributes to sloppy playing. The majority of band members still have excellent rehearsal discipline, but a small handful thinks that it is a pep rally.

The breaks in the rehearsal present another problem. Most schedules have a 30-minute break at mid-morning and mid-afternoon. This is too short a time to go to town and much too long to just sit in an auditorium. I much prefer to take a ten-minute break every hour. This is plenty of time to visit the water fountain and the restroom. During a four-hour morning session this gives 30 minutes of breaks. During a three-hour morning session the breaks would be 20 minutes. I have found that students stay fresher with a break every hour than a 30-minute break in the middle.

Programming for the all-state is my biggest concern and problem to solve. The program must do three things: be appealing to the players, appealing to the audience, and be of high musical quality. Programming must be chosen and placed in an order that produces a dramatic concert. I have found that five works is just right. I choose three large strong works and place these 1-3-5. Of the three I choose the best opener and the best closer. For two I select a slow work and for four I put a march or a light piece. If I have overshot the playing level of the band, I might delete the difficult work in the middle and spend more time on the others.

No matter the reason to start the all-state movement, it has grown into one of the best activities we have. To start a concert program and finish it three days later gives students an experience that they can get nowhere else. With the right conductor and the right programming of good literature it will prove an experience that students will remember the rest of their lives. (2003)6

The following excerpts are from W. Francis McBeth’s The Complete Honor Band Manual – A Guide for the Preparation and Organization of Honor Band Clinics:

• The Opener

“Many years ago I was reflecting about the past year of clinic concerts and wondering why some of the opening works had been a bit shaky when they should not have been. The first or opening work cannot be shaky or it will affect the entire concert because fo the destruction of the players’ confidence. It dawned on me that the three concerts that had had a shaky or not up to par first work all pulled the curtain on the band. The following year I experimented with this phenomena and learned that when high school students are seated behind a closed curtain, they feel warm and secure; but when the curtain is opened, the adrenaline hits their spines, bounces off their brains, and dries out their mouths.

“When a band is seated with an open curtain, the players have a chance to warm up in full view of the audience, to give a slight wave to mother, and to feel comfortable before the downbeat.”

• The Great Escape

“Get to the church on time – or don’t make the plane departure an Olympic event. The clinician is tired, you are tired, but go ahead and get up and take the poor man to the airport. To leave the tired clinician to the mercy of an airport bus, which God only knows when it will arrive or get to the airport, isn’t the best end for the clinic.

“I once waited for an airport bus that never arrived. I ended up stopping a man that I recognized from the clinic and asked for help. He got me to the airport (30 miles away) in a 20-year-old car with smoke billowing from under the dash. The car would not stay running unless I held two wires together the entire trip. I’ll never forget his kindness – never knew if he ever got back. I doubt it. I don’t know how he could have shifted and held those two wires together while driving in that snowstorm. I wish I had written his name down.” (2003)6

Random Reflections

• It is difficult to learn if you are not enjoying the experience.

• It is a shame that when teachers and doctors finally figure out how to really do it, it is time to retire.

• When I hear Mozart, I hear a man touched by the gods; when I hear Beethoven, I feel that I am shaking his sweaty hand. That’s why I love Beethoven. He was the first composer to combine direction with the catastrophic.

• In my opinion one’s best work is achieved through pressure. When there is a lack of pressure, I take a nap.

• When you step on the podium, whether it is in front of a high school all-state, the Marine Band, or the Chicago Symphony, the players will decide in the first 15 minutes of the first rehearsal whether you have got it or not. If you don’t do it then, it can take days to alter a first impression. It is the same in teaching except it will take not days but weeks to change the first class period impression.

• 60% percent of the great music shown us by our teachers and heard in a concert is very dull and boring. Of the remaining 40%, 30% is quite good, the remain 10% is great music, and 5% of this is so superb that it is almost not of this world.

• There also can come a time when discouragement is necessary to prevent disaster, but it must be a last resort, and the teacher must be completely correct. I had a composition major who was smart and a hard worker, but after a year of study I had to discourage him. When I did it, he had tears running down his cheeks, and I felt terrible for weeks. The following year after he had changed his major, he came to me and again with tears in his eyes, hugged and thanked me and said that for the first time in his college career, he was happy.

• The desire for knowledge, whether it is in music or animal husbandry, is so exciting. The acquisition of knowledge is an excitement that cannot be matched with wealth or position.

• It’s a frustrating time in life to work with younger teachers who have never heard of Booganville, Guadalcanal, the Ardeine, and Audie Murphy. The spiritual gap is huge and we will never completely understand each other.

• If it were not for football and graduation, most universities would not want a music department.

• How has teaching changed? To quote Lou Holtz, “students today (1997) are concerned with rights and privileges. Twenty-five years ago they were concerned with obligations and responsibilities. There is a lot of truth in what he said, but there are always one or two students each year who have the commitment, and these few make it all worthwhile. (2000)7

References

1 It’s All in the Score, An Interview with W. Francis McBeth by Jeffrey Renshaw, August 1998, p. 10.

2 Rehearsing Efficiently by W. Francis McBeth, August 1997, p. 40.

3 Band Music and the Paper-Plate Mentality, An Interview with W. Francis McBeth by Roger Rocco, December 1991, p. 12).

4 Interpretation, Unlocking the Drama in Music by W. Francis McBeth, December 1992, p. 14.

5 The Creative World by W. Francis McBeth, November 1994, p. 12.

6 The Growth and Change in All-State Bands over the Past 50 Years by W. Francis McBeth, August 2003, p. 12.

7 50 Random Reflections on Music and Teaching by W. Francis McBeth, June 2000, p. 17.