My goal is to perform the complete Sigfrid Karg-Elert 30 Caprices in a lecture recital. I have known, played, and taught these pieces for many years, but have never thought seriously about playing them all in a row, one after another, until now. The question is how to go about practicing this task. Should I practice five caprices a day, six days a week, or practice 15 caprices on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and the other 15 caprices on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday? Because there are less than six weeks to reach my goal, I thought I would try a new practice tactic.

My goal is to perform the complete Sigfrid Karg-Elert 30 Caprices in a lecture recital. I have known, played, and taught these pieces for many years, but have never thought seriously about playing them all in a row, one after another, until now. The question is how to go about practicing this task. Should I practice five caprices a day, six days a week, or practice 15 caprices on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and the other 15 caprices on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday? Because there are less than six weeks to reach my goal, I thought I would try a new practice tactic.

If I practiced each caprice to the fullest, I would need more practice time than I have, so I decided to use the Power Practice technique and follow the plan below:

I set a timer on five minutes and practiced each caprice as creatively as I could for five minutes and then went on to the next one. The first day was spent on Caprices 1 – 15, and the second day on numbers 16 – 30. Time-wise this created one session of one hour and fifteen minutes each day to practice half of the Caprices, each for five minutes. Some days I might be able to do all the caprices in two one-hour-and-a-half sessions. This was certainly possible. At the end of each day, I would play through the opposite day’s 15 caprices in a row to keep the music fresh in my memory. This took another 20 to 25 minutes. But once again, an additional 25 minutes was certainly possible.

The first day of power practicing achieved better results than I would ever have dreamed. I was able to get into deep practicing quickly, over and over again. As I was assessing my success, I thought of Malcolm Gladwell’s book Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. Gladwell is a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine and author of four New York Times best sellers.

In Blink he discusses the quality of decisions we make in the blink of an eye. He says that it takes only two seconds to jump to a series of conclusions. The book is about those two seconds. The term he coined for this event is Rapid Cognition.

As a society we have been taught over and over again that haste makes waste. We learn that it is safer and better to gather and compare information, and only after careful assessment, make an informed decision. Gladwell disagrees. He suggests “there are lots of situations – particularly at times of high pressure and stress – when haste does not make waste, when our snap judgments and first impressions offer a much better means of making sense of the world.” Moments of high pressure and stress are exactly what performing is all about.

Haste Makes Waste

In order to successfully use this theory in practice, a flutist should have several basic skills. First is the ability to play the flute on an advanced level. This includes understanding the set-up (body alignment, balance of flute in hands, and how the flute works), breathing strategies, articulation, vibrato usage, spinning a line, dynamic control, basic musicianship, theory, historical context, and a knowledge of each composer’s work.

The flutist must also have an arsenal of practice techniques to plug into each practice session. If you don’t have practice strategies at hand, you will use up your five minutes just figuring out what to do. All these elements take years to gather and put into practice. So here the adage haste makes waste is still relevant. If these things are not in place, then the tried and true older practice style of breaking things down into chunks and practicing many repetitions in a variety of tempos and dynamics is the best choice.

Haste Does Not Make Waste

However, if you play at an advanced level and have well-established practice techniques, it is possible to use what I call Power Practice. In performance we don’t play by reading one note after another; this sounds plodding and stodgy. A great performer glances at the notes and can immediately recall what he has spent hours on in earlier practice sessions. It only seems logical to practice this skill to replicate what happens on stage.

Fastforward Practice

When I was discussing the Power Practice technique with Samantha George, Lawrence University violin professor, she mentioned that she uses Fastforward Practice a few weeks before an upcoming performance. The idea comes from the fastforward button on a DVD player, which speeds up the action so you may find a scene in a movie quickly. Fastforward Practice tests the Rapid Cognition. Practice chunks followed by rests at a tempo that is twice as fast as prescribed. If you have problems in fastforward chunks, you know where you might stumble in performance. It is in these passages, you should spend time re-examining and analyzing. This is a variation of the power practicing technique.

30 Caprices And Power Practicing

Here are some practice techniques to use in Caprices 1 – 15. They are only suggestions, and as you experiment, you will have many more to add to the list. Remember, each Blink episode lasts five minutes. Set your timer, and when it rings, go on to the next Caprice. Your entire practice session will be 75 minutes (5 minutes x 15 caprices).

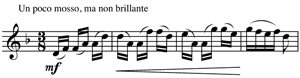

Caprice 1: In tempo play the first three beats of each measure followed by a rest on the fourth beat. What do you notice about the motive? Is it used in every measure? What is the chord outlined by the motive? If the motive is not present, what is the characteristic of the material in the measure?

Caprice 2: Play only the measures in which the notes are slurred by 2s. You should play the second note softer than the first. Chunk the entire caprice in hemiola (by two counts with a rest in between each segment).

Caprice 3: Play only the palindromes followed by a rest or silence. (Webster’s: Palindrome: a word, verse, sentence, or number that reads the same way backwards or forwards. In music I use this term to indicate passages that read the same way backwards or forwards. If there are only three notes, the middle note is a non-chord tone called an upper or lower neighbor.) Often, bringing out the palindromes makes you sound more musical.

.jpg)

Caprice 4: Play each measure followed by a quarter rest. In Baroque music, the implied rhythm of a 3/4 bar is either a half note followed by a quarter (long, short inflection) or a quarter followed by a half note (short, long inflection). The half note meaning is implied if the two beats are either four notes of a scale or a chord. Chunk the 5/4 and 3/2 measures by the note beaming. (Beaming is the line that connects the eighth notes.)

Caprice 5: Play (chunk) two beats and rest two beats. Follow the dynamic and articulation marks for each chunk. The silence will give you time to better organize the dynamics and articulation marks. Exaggerate the dynamic and articulation marks because in performance you naturally lose some of the effect. Play each chunk on one breath. Notice the variety of articulation patterns with each chunk. These varieties of articulation patterns are what I call the Magic 8s.

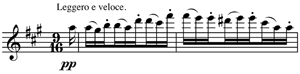

Caprice 6: Let it swing. Play starting on the second eighth note of the measure, concluding on the first eighth of the next measure followed by a rest. (In this practice session, omit the measures that do not have six eighth notes in them.) Either make a crescendo to the first beat or a diminuendo to the first beat. There should be enough time to do each way.

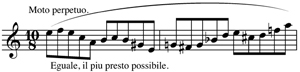

Caprice 7: Play each group of five notes followed by a rest as fast as you can. The second time through, tongue in the following pattern: TKTKT or TTKTK.

Caprice 8: Chunk three beats followed by a rest. Be sure the first note of each mordent is on the beat, not before it. Play later on the beat to achieve this accuracy.

Caprice 9: Chunk by measure followed by a rest. Notice the variety of articulation patterns used with six notes. The first time through use a T on the first note after a slur. The second time use a K on the first notes after a slur.

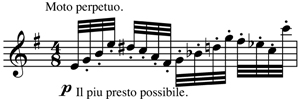

Caprice 10: Practice the “Mannheim sigh” figures. Play in 2/4 time. The first note will be on the and of two, and the next two notes will be on the first beat. Rest for an eighth note and proceed throughout the caprice. Follow the tongue one, slur two indication as in lift, strong weak. If you wish, for variety, place a trill on the 1st beat (note indicated by strong).

Caprice 11: The first time play only the double- or triple-tongued notes. The second time play only the slurred notes. Place a rest in between each group (chunking).

Caprice 12: Play only the notes that are slurred. Rest on the tongued notes.

Caprice 13: Play only the notes with the stems up. Then play only the notes with the stem down.

Caprice 14: Chunk by four notes followed by a rest. Can you identify the chord in each group of four? Because of rhythmic displacement in measures 9 and 10, adjust to chunk by the beaming of the notes.

Caprice 15: Play only the double stemmed notes forte making a rest where the single stemmed notes are. Then play only the single stemmed notes piano.

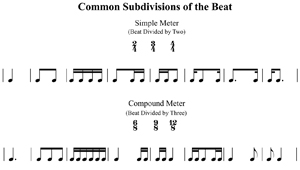

Other general practice techniques you might consider involve practicing passages in different rhythm configurations. Check to see if the Caprice is in simple or compound time and use the chart below for suggestions.

The final sentence of Karg-Elert’s “The Logical Development of Modern Figuration” concludes: “The author believes herewith to have given hints which should cover all the possible figurations which may occur in existing modern works.”

For years I have thought that hints was a strange word choice for a scholarly treatise. I usually associate the word with a puzzle. Then it occurred to me that the 30 Caprices are one big puzzle. I had also wondered why he would chose to conclude the set with a Chaconne (a Baroque compositional device), when in the preface he states: “The present Caprices take the Classical technique of Bach, Handel, and Mozart as their starting point and pass rapidly to the style of today.”

Today a chaconne is a rarely used compositional device. But, if this were a giant puzzle, then the chaconne theme of the four descending notes is the final clue for the player (if the flutist hasn’t already figured it out). The above practice suggestions will help you find the chaconne theme in each caprice. Karg-Elert either uses the four note chaconne ground ascending/descending by diatonic, chromatic or whole tone configuration. Some-times the four notes occur at the beginning of each beat or in some beat pattern as in the first and third beats of a two bar measure. I don’t want to spoil the puzzle for you – the joy is in figuring it out for yourself. These caprices were written for Karg-Elert’s friend Carl Bartuzat, principal flutist of the Leipzig Theater and Gewandhaus-Orchestra. What a wonderful gift for a professor of theory and composition to give to his friend and to us.

Karg-Elert Caprices

There are several editions of the Caprices, including Southern Music Co., Master Music, International Music Co., Cundy-Bettoney, and Kalmus, and Urmusik Edition. With the exception of the Urmusik Edition all of the other publication are printed from the same plates.

The Cundy-Bettoney edition is noteworthy because it includes Karg-Elert’s Preface of 1919 and his 10-page guide “The Logical Development of Modern Figuration.” The Southern Music edition is part of The Modern Flutist, which also includes the 8 Etudes de Salon of Donjon and various orchestral excerpts.

The Urmusik Edition was published in 2008, edited by the assistant professor at the University of Minnesota in Duluth flutist and scholar Lorie Scott. It includes the Preface and the Guide to modern figuration, as well as a short bio of Karg-Elert, Scott’s analytical notes, and a short bibliography. Each caprice has new typesetting, is printed on a separate page, and Scott has corrected many of the wrong notes, although there remain several questionable notes.

Scott writes, “often characterized as technical repertoire, I hope that you ultimately come to love the Caprices for their inherent musical value, bringing them to the performance stage more frequently. A selection of caprices functions beautifully as a set of short character pieces for unaccompanied flute within a recital.” I totally agree. The Karg-Elert Caprices and the Telemann Twelve Fantasias are always on my music stand.