He who knows best knows how

little he knows. Thomas Jefferson

Some time ago, I received a letter from Norman Brentley, a flutist and teacher in Washington D.C.:

"I wonder if you could please help me answer a question about trills in the Mozart Concerto in G Major. When I studied that piece at Oberlin and several times since in performing it, I remember playing all the first-movement trills from above and on the beat…period!

Someone here agrees with that premise, except when the note before the trill is the same pitch as the first note of the trill. In that case, the trill is played with no special preparation, i.e., the third bar of the flute solo part, where the beginning of beat four is a C instead of a D. I do realize that the interpretation of ornaments changes over time. I am, however, looking for a standard on which I can hang my argument. What would have been appropriate for that period, and which approach would you use when playing that same piece today?”

I went back to historical sources: A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing written by Leopold Mozart in 1756 (Chapter IX is about Appoggiaturas, grace notes, and Chapter X is about the Trill) and Johann Joachim Quantz’s Essay On Playing the Flute (1752). W.A. Mozart was born the year that Leopold’s book was published and four years after Quantz’ book was published.

On Trills

I am afraid that a standard cannot be given for all instances.

In the case he mentions, the D in the third bar of the flute part is probably a written-out appoggiatura or vorschlag (preparation) so there is no need to repeat it at the start of the trill. However, if a player wants to do so, he won’t be taken to the Bastille.

All cadential trills should start on the upper note, whether written or implied, and they should end with a nachschlag (termination) as close as possible to the tonal note. This was appropriate for this measure in Mozart’s day, and it is still appropriate today.

If a trill is not part of a cadence but simply an ornament or a passing embellishment, it makes sense to use a mordant or a turn. An appoggiatura plus a trill followed by a termination would occupy too much space and slow down the musical discourse for no good stylistic reason.

All rules have exceptions, as lawyers well know: in measures 71 and 189, it seems appropriate to enhance the tension of the chromaticism by not preparing the trill from the top note.

mr. 189, Urtext

mr. 189, Urtext

mr. 189 performed (no trill preparation)

There are also inconsistencies, even in the Urtext (original printing) edition, which shows the flute part plus the tutti violin parts. The melodic material in measure 22 in the violins and measure 78 in all the string parts is the same, yet the ornamentation is different. Measure 40 of the flute part has no trill, but measure 158, which is the same figure, has a trill. The same is true of measure 71, which has a trill and measure 189, which has none.

It is difficult to know if these inconsistencies are typos, copier’s errors, or a deliberate difference intended by Mozart. Even in Mozart’s time, differences were acceptable. Certain note configurations were easier than others on the one-keyed flute used by Quantz and Mozart. The prime requirement was to play elegantly and comfortably.

Grace Notes

A grace note is a note written before the beat. When properly notated, it is a little note with or without a slash through the stem and is printed before the note it precedes. The French called these petites notes. It is not a very descriptive term, because the same symbol (a small note next to a regular size note) can be many things.

The general rule for appoggiaturas (petites notes, grace notes) was that they are always played long – except when they are played short:

• It is short if the grace note is followed by an octave or a wide interval (up or down):

Adagio ma non troppo m. 49

Adagio ma non troppo m. 49

• It is short if the grace note is on repeated notes of the same name.

.jpg)

• It is short if the grace note is placed on the shortest value of the piece (on a 16th in an Allegro or on a 32nd in an Adagio)

• It is short if the grace note is on a syncope, because a long grace note would weaken it.

• It is short if the grace note is on an appogiatura, because a long grace note would also weaken the harmonic tension.

In English we use the term grace note to define these little notes in Mozart, but as usual in musical matters, the Italian terms are the most evocative and useful. They describe the ornaments most used by Mozart, and tell us something about how to treat them.

Appoggiatura comes from appoggiare, to lean and implies harmonic tension and release, a vital phrasing element.

A quick appoggiatura is a passing note bearing little tension and occurring immediately near the main note.

Acciaccatura means two notes so close that both seem struck at once as in keyboard music.

Passing note (agréments, ornements in French or embellishments in English) means of purely decorative nature, without structural or expressive necessity.

The grace note, therefore, is a generic English term that designates any ornament.

Verzierung, the German word for ornament, also lacks specificity. Remember that there were rules, but they were more like loose guidelines, variable according to the player, his preferences, and his geographic origin. Also, each composer provided a trill chart that included symbols and how to play them. Performers consulted the charts and used them as guidelines. The tempo of the music also affected the amount of ornamentation to use.

There are also other little notes. These should be interpreted as one of the following in music of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven.

Sometimes the ornaments that look like grace notes (as in the example above) are printed with a slash across the stem. This is incorrect. In 1752 Quantz said that “it is of little importance whether they (the grace notes) have one or two crooks”.

How do you know which ornament is intended? That’s a good question.

This measure can be played at least two ways. It appears twice in the flute part and twice in different forms in the tutti part,

.jpg)

or as many editions show

May I share a mystery? The urtext edition shows in many instances, but not always, this figure:

It is usually played comfortably as:

I have never understood why the urtext writing is so awkward and therefore so seldom used. (This is how the urtext version would be played if interpreted literally.)

I remember in my young days that it was considered elegant to lean on the first note of a 16-note group so the passage was played like this:

I did not know for sure, so I tried all three ways, and if one felt better, I used that for a while. Interpretation has a tendency to go with fashion, too. Why not choose the one you think sounds best? (This may not be the one that’s easiest to play.)

If notated properly, the final trill in the example above (cadential) is a little note followed by an 8th note and two 16ths. There will be no slash through the stem of the little note.

You might ask why Mozart used an alternate notation sometimes instead of being consistent. Perhaps he didn’t care which way he wrote it. Consistency is the conviction of the mediocre. Or perhaps the inconsistencies were typos.

Also, Mozart might have neglected to proof his work for lack of time, especially for subsistence commissions, for which he was always late, such as the flute concertos. We might never know, because Mozart’s autograph has not been found to this day. Consequently there are many different versions in print, with their peremptory solutions. The only reliable version is the original printed edition as reproduced in the Urtext, with its original inconsistencies. I use the Bærenreiter Urtext to teach, even though I find that it shows all of the parts, flute and tutti alike, cumbersome.

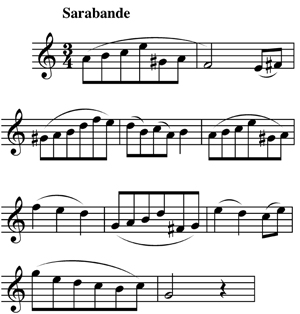

Two remarks come to mind: I recently visited with Barthold Kuijken, who is one of the best traverso players of our day. I was interested in his views about ornamentation and the interpretation of grace notes. He plays an extremely ornamented “Sarabande” in the Bach Partita, and he said that nobody is required to imitate him, because that’s his take on it and to each his own. His “Allemande,” in contrast, is very sober and straightforward.

My other remark is more contemporary: I had the good fortune to play with Jolivet, Boulez, and many others. I remember Poulenc vividly and what he said about his Sonate. When I see modern editions of it and hear the stuff people do with it, I have doubts about myself and about his legacy, a mere half-century after his death. With Mozart we are dealing with more than two centuries since 1791 when Mozart died.

Home > Mozart Trills

Mozart Trills

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

He who knows best knows how

little he knows. Thomas Jefferson

Some time ago, I received a letter from Norman Brentley, a flutist and teacher in Washington D.C.:

"I wonder if you could please help me answer a question about trills in the Mozart Concerto in G Major. When I studied that piece at Oberlin and several times since in performing it, I remember playing all the first-movement trills from above and on the beat…period!

Someone here agrees with that premise, except when the note before the trill is the same pitch as the first note of the trill. In that case, the trill is played with no special preparation, i.e., the third bar of the flute solo part, where the beginning of beat four is a C instead of a D. I do realize that the interpretation of ornaments changes over time. I am, however, looking for a standard on which I can hang my argument. What would have been appropriate for that period, and which approach would you use when playing that same piece today?”

I went back to historical sources: A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing written by Leopold Mozart in 1756 (Chapter IX is about Appoggiaturas, grace notes, and Chapter X is about the Trill) and Johann Joachim Quantz’s Essay On Playing the Flute (1752). W.A. Mozart was born the year that Leopold’s book was published and four years after Quantz’ book was published.

On Trills

I am afraid that a standard cannot be given for all instances.

In the case he mentions, the D in the third bar of the flute part is probably a written-out appoggiatura or vorschlag (preparation) so there is no need to repeat it at the start of the trill. However, if a player wants to do so, he won’t be taken to the Bastille.

All cadential trills should start on the upper note, whether written or implied, and they should end with a nachschlag (termination) as close as possible to the tonal note. This was appropriate for this measure in Mozart’s day, and it is still appropriate today.

If a trill is not part of a cadence but simply an ornament or a passing embellishment, it makes sense to use a mordant or a turn. An appoggiatura plus a trill followed by a termination would occupy too much space and slow down the musical discourse for no good stylistic reason.

All rules have exceptions, as lawyers well know: in measures 71 and 189, it seems appropriate to enhance the tension of the chromaticism by not preparing the trill from the top note.

mr. 189 performed (no trill preparation)

There are also inconsistencies, even in the Urtext (original printing) edition, which shows the flute part plus the tutti violin parts. The melodic material in measure 22 in the violins and measure 78 in all the string parts is the same, yet the ornamentation is different. Measure 40 of the flute part has no trill, but measure 158, which is the same figure, has a trill. The same is true of measure 71, which has a trill and measure 189, which has none.

It is difficult to know if these inconsistencies are typos, copier’s errors, or a deliberate difference intended by Mozart. Even in Mozart’s time, differences were acceptable. Certain note configurations were easier than others on the one-keyed flute used by Quantz and Mozart. The prime requirement was to play elegantly and comfortably.

Grace Notes

A grace note is a note written before the beat. When properly notated, it is a little note with or without a slash through the stem and is printed before the note it precedes. The French called these petites notes. It is not a very descriptive term, because the same symbol (a small note next to a regular size note) can be many things.

The general rule for appoggiaturas (petites notes, grace notes) was that they are always played long – except when they are played short:

• It is short if the grace note is followed by an octave or a wide interval (up or down):

• It is short if the grace note is on repeated notes of the same name.

• It is short if the grace note is placed on the shortest value of the piece (on a 16th in an Allegro or on a 32nd in an Adagio)

• It is short if the grace note is on a syncope, because a long grace note would weaken it.

• It is short if the grace note is on an appogiatura, because a long grace note would also weaken the harmonic tension.

In English we use the term grace note to define these little notes in Mozart, but as usual in musical matters, the Italian terms are the most evocative and useful. They describe the ornaments most used by Mozart, and tell us something about how to treat them.

Appoggiatura comes from appoggiare, to lean and implies harmonic tension and release, a vital phrasing element.

A quick appoggiatura is a passing note bearing little tension and occurring immediately near the main note.

Acciaccatura means two notes so close that both seem struck at once as in keyboard music.

Passing note (agréments, ornements in French or embellishments in English) means of purely decorative nature, without structural or expressive necessity.

The grace note, therefore, is a generic English term that designates any ornament.

Verzierung, the German word for ornament, also lacks specificity. Remember that there were rules, but they were more like loose guidelines, variable according to the player, his preferences, and his geographic origin. Also, each composer provided a trill chart that included symbols and how to play them. Performers consulted the charts and used them as guidelines. The tempo of the music also affected the amount of ornamentation to use.

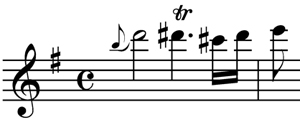

There are also other little notes. These should be interpreted as one of the following in music of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven.

Sometimes the ornaments that look like grace notes (as in the example above) are printed with a slash across the stem. This is incorrect. In 1752 Quantz said that “it is of little importance whether they (the grace notes) have one or two crooks”.

How do you know which ornament is intended? That’s a good question.

This measure can be played at least two ways. It appears twice in the flute part and twice in different forms in the tutti part,

or as many editions show

May I share a mystery? The urtext edition shows in many instances, but not always, this figure:

It is usually played comfortably as:

I have never understood why the urtext writing is so awkward and therefore so seldom used. (This is how the urtext version would be played if interpreted literally.)

I remember in my young days that it was considered elegant to lean on the first note of a 16-note group so the passage was played like this:

I did not know for sure, so I tried all three ways, and if one felt better, I used that for a while. Interpretation has a tendency to go with fashion, too. Why not choose the one you think sounds best? (This may not be the one that’s easiest to play.)

If notated properly, the final trill in the example above (cadential) is a little note followed by an 8th note and two 16ths. There will be no slash through the stem of the little note.

You might ask why Mozart used an alternate notation sometimes instead of being consistent. Perhaps he didn’t care which way he wrote it. Consistency is the conviction of the mediocre. Or perhaps the inconsistencies were typos.

Also, Mozart might have neglected to proof his work for lack of time, especially for subsistence commissions, for which he was always late, such as the flute concertos. We might never know, because Mozart’s autograph has not been found to this day. Consequently there are many different versions in print, with their peremptory solutions. The only reliable version is the original printed edition as reproduced in the Urtext, with its original inconsistencies. I use the Bærenreiter Urtext to teach, even though I find that it shows all of the parts, flute and tutti alike, cumbersome.

Two remarks come to mind: I recently visited with Barthold Kuijken, who is one of the best traverso players of our day. I was interested in his views about ornamentation and the interpretation of grace notes. He plays an extremely ornamented “Sarabande” in the Bach Partita, and he said that nobody is required to imitate him, because that’s his take on it and to each his own. His “Allemande,” in contrast, is very sober and straightforward.

My other remark is more contemporary: I had the good fortune to play with Jolivet, Boulez, and many others. I remember Poulenc vividly and what he said about his Sonate. When I see modern editions of it and hear the stuff people do with it, I have doubts about myself and about his legacy, a mere half-century after his death. With Mozart we are dealing with more than two centuries since 1791 when Mozart died.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michel Debost

Michel Debost is the former principal flutist of the Orchestre de Paris and flute professor at the Paris Conservatory and Oberlin Conservatory. He is the author of The Simple Flute.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Summer Camp Directories

Nothing Happens By Accident A Conversation with Trudy Fraase Wolf

ADVERTISEMENT

Order your Marching and Color Guard Awards this Fall!

Orders may be placed through the online store, by email (awards@theinstrumentalist.com) or by calling 888-446-6888.