.jpg) When Aaron Copland’s Duo for Flute and Piano was premiered in late 1971, the composer was 70 years old. He had spent the previous decade writing mostly in the serial, atonal mode of the time, and in many ways his Duo was a throwback to the 1940s when his most popular ballet scores, Appalachian Spring and Billy the Kid, were composed. Duo was commissioned by a large group of students and friends of William Kincaid, longtime principal flute of the Philadelphia Orchestra, who had died in 1967. The work is dedicated to his memory. Flutist Elaine Shaffer and pianist Hephzibah Menuhin premiered the piece, and Shaffer recorded it in early 1973 with Copland himself at the piano.

When Aaron Copland’s Duo for Flute and Piano was premiered in late 1971, the composer was 70 years old. He had spent the previous decade writing mostly in the serial, atonal mode of the time, and in many ways his Duo was a throwback to the 1940s when his most popular ballet scores, Appalachian Spring and Billy the Kid, were composed. Duo was commissioned by a large group of students and friends of William Kincaid, longtime principal flute of the Philadelphia Orchestra, who had died in 1967. The work is dedicated to his memory. Flutist Elaine Shaffer and pianist Hephzibah Menuhin premiered the piece, and Shaffer recorded it in early 1973 with Copland himself at the piano.

Reviews of the first performances called it “pastoral and elegiac in mood. . .a chamber music gem” (Time Magazine, 1/1/73); “a tightly composed piece. . .sonorities are spare, even hard-edged at times, with no tricks. . .a lightweight work of a masterful craftsman” (Michael Steinberg, Boston Globe, January 1972). Of the New York premiere, the New York Times said: “Beneath the surface charm lies the composer’s customary sophisticated sense of narrative development, rhythmic ingenuity and keen ear for instrumental color” (Peter Davis, NYT, October 1971). The Boston Globe article quoted above also emphasized, like the New York Times review, Copland’s consistently high standard of composition, saying “he has never written inattentively nor, for that matter, without huge signs saying ‘only by Aaron Copland.’”

These early reactions to Duo are important to understanding this work. Although it is technically quite manageable and expressively clear, there is much, both on the surface and underneath, that is elusive unless performers pay very careful attention to the details.

My own first performance of the work took place just a few years after its premiere, when I was very young in years and experience. I was in Italy and had not yet heard another interpretation. I remember feeling disappointed in the piece, thinking it a bit shallow and not very compelling. The review of my concert confirmed these feelings. Little did I realize then that it was my performance that was shallow and unconvincing!

I now cringe to think of my youthful presumption to know better than Aaron Copland, but it was an important lesson in retrospect. When I decided to record Duo in 1994 for my solo C.D. American Flute (by which time the work was a classic), my attitude had evolved. As the pressure and heightened responsibilities associated with a recording loomed before me, it was clear that, in order to be true to the composer’s score, I needed to spend careful hours studying the music.

Hosts of etudes and other studies came to mind quickly for the previous article on Muczynski’s Sonata Op. 14, but not so for Duo. This fact just confirmed my sense of the work as a tough nut to crack. Turning pages of the score, I kept waiting for some obvious etude collection or composer to leap out at me. Only after putting the music down and asking the question, What is it that’s so demanding about this piece? Did answers come.

The Challenges

Technically, the hurdles are embouchure flexibility, intonation, a subtle array of articulations, and the facility to change tone color quickly. Expressively, all those technical elements are the tools necessary for a great many fast-moving sections that are like brief scenes throughout the piece. Though Copland was against programmatic interpretations of his absolute music, his natural narrative qualities (as the reviewer noted) are very evident in Duo from beginning to end. The sense of a story or set of scenes unfolding is especially strong in the first movement, where I find at least eight character changes that require quick tone quality and/or articulation shifts.

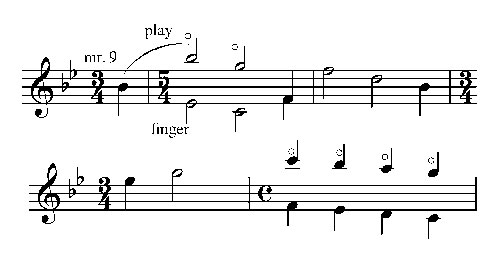

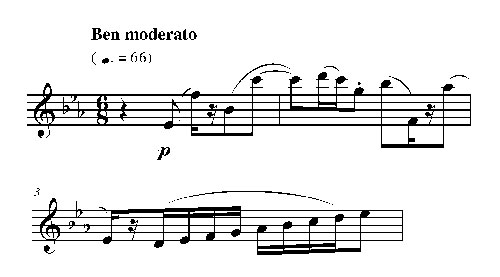

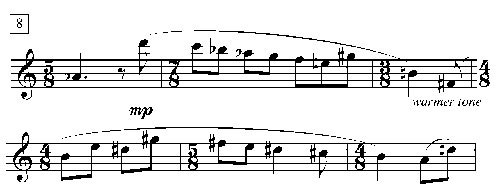

The marvelous opening recitative could not be simpler in interval structure, nor more difficult in execution. Copland’s trademark use of open 4ths and 5ths combined with thirds immediately puts the flutist’s intonation to a rigorous test. Singing and playing the intervals (see Muczynski article, Flute Talk, October, 2008) is one way to become open and resonant, and it requires listening closely to these pitches. For pitches from middle G and above, use harmonics to find the best embouchure position.

For example, the pickup to measure 10 leads to an octave B flat. Play the first B flat, and as you go to the octave, finger low E flat while playing the B flat partial above it. The correct lip angle and air speed is necessary to get the right partial. Finger low C for the next G, and so on. The fingering for measures 9-13 is shown below the written notes. Finger the lower note when there are two, but lip up to the upper note. Play this passage and similar ones with harmonic fingerings, then repeat immediately with real fingerings, trying to maintain the same embouchure position, lip angle, and air speed, which should be faster than you might normally use because of the resistance from the fundamental.

The opening’s expressive aspect might cause you to question this faster air speed, considering the expansive, prairie-like nature of the music, which could be conveyed with a low-resistance sound. However, the air speed produced by the harmonic exercise is the basis for pitch security and core tone. It is quite possible to put more air behind the sound rather than in it. In this case, you will feel more pressure from the air inside, and it will support the tone and pitch. At the end of the recitative section (#2), you should feel that there is air to expel.

For the opening, it is important to know what kind of tone you want and also how to get it. Some people think in terms of colors, while others use descriptive words such as open, closed, dark, bright, and hollow. The other important observation is the freely, recitative style marking. I have heard few interpretations of this opening that actually gave a sense of freedom and conversational style, which is what the indication means. It is difficult to look at the page, with its clearly marked meter changes and quarter- and half-note values, and move outside those bar lines. It would be easier if the note values were smaller and had more rhythmic activity. Writing out the beginning until #1 with no meter or barlines allows you to see the phrase direction more clearly and pay more attention to the rise and fall of the line.

Playing opera in Italy early in my career was the best lesson I ever had in learning to interpret music. We had to be fluid and able to adapt phrasing to follow singers who went many places the notes never hinted at. When you do everything in your power to escape from our beat-oriented, literal upbringing of reading music, you will discover how much musical expression comes from stretching, compressing, and suspending the beat.

Metronome Markings

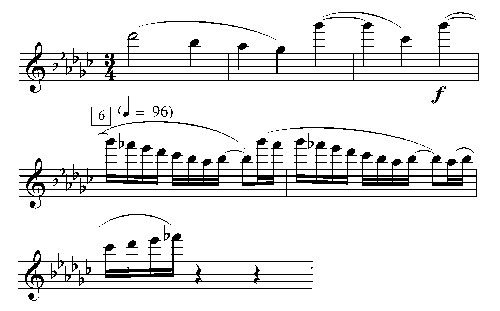

We often complain that composers are careless or unreasonable with metronome markings, but of the many details in Duo that require attention, tempo markings are at the top of the list. The first movement has six different metronome marks, and they each refer to the character of their respective sections. For instance, the indication at #2 of a dotted-half = 60 supports the verbal instructions of Much faster (always flowing), with delicacy. Seven bars later at #3, Copland wants players to remove most of the beats and play in one to the bar in order to achieve a flowing quality.

The sudden tempo change at #6 is an almost stilted moment, and 96 is an awkward tempo – neither slow nor fast.

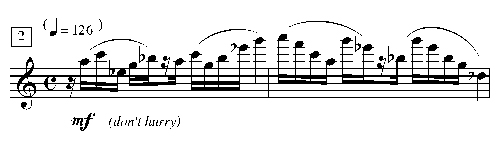

The tendency is to take it too fast, but awkwardness is part of the character of this section, as if a country bumpkin has suddenly entered the scene. At #8 the tempo indication is 84, just 12 notches under the previous 96 section. In a lesser composer, this would seem unnecessarily controlling. With Copland it complements the verbal instructions relax the tempo and with charm. This smooth and lyrical section gathers energy and climaxes at #10 with very fast 32nd-note runs, but Copland reminds us to be soave six bars before #10 and then don’t hurry on the runs themselves.

At #11 he marks quarter = 112, then changes to dotted half = 60 a few bars later, which means playing three beats to the bar at #11 and accelerating to one to the bar six measures later. It all fits perfectly with the music and, if you feel controlled at all, it is by the hand of a master, who knows exactly what the music is doing and wants to be sure that you do too.

Suggested Exercises

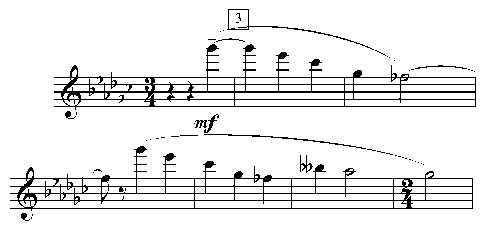

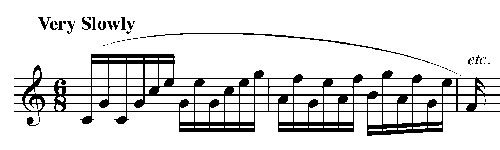

Embouchure flexibility exercises for the first and third movements, where legato downward intervals are prevalent, are found in the following collections: Soussmann’s 24 Grand Studies (#19), Marcel Bitsch 12 Etudes (#2 and 11), and Andre Maquarre’s Daily Exercises (#2, 3, & 7). Soussmann’s study in E flat is also included in Trevor Wye’s Tone Book, vol. 1. Wye suggests using the beginning of the study very slowly for playing large intervals with a full and rich sound. The original is faster but has the same goal.

The relatively modern French Bitsch etudes focus on flexible embouchure, #2 specifically for “flexibility of the lips” in a quiet setting and #11 “for intervals” with more meter and rhythmic variation.

Maquarre’s Daily Exercises employ the conventional interval structure found in Duo without the modern harmonic underlay. Maquarre’s #2 is a good workout in slurred ascending and descending fifths and sixths.

Exercise #7 of Maquarre has descending thirds and sixths with an upward swing that is close to the note groupings at #2 in Duo’s third movement.

.jpg)

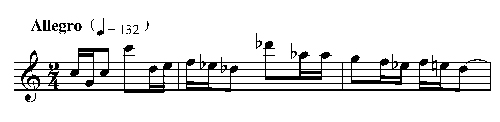

Here I think of Copland’s reminder don’t hurry (quarter = 126, after quarter = 138 at the movement’s start) is cautioning players to keep this passage smooth and cool. After the hoedown mood of the beginning, with its pointed articulation and jagged rhythms, the subtle tempo change is difficult to negotiate without exercising emotional control over the legato arpeggiated figures. This is accomplished with technical control of the lip movement (very slight and held primarily in the position of the lowest note of the figure) and an evenly parceled-out airstream.

Movement One

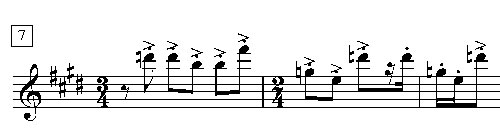

Attention to articulation marks is also very important in Duo in order to define the character of each section. The first movement is largely legato, but the middle section (#7-10) reveals Copland’s meticulous care in choice of tonguing styles.

At #7 he writes a staccato and accent over every note, but five bars later he removes the dot. At first glance it looks as though we should play these accented phrases the same way, but the context and Copland’s other indications show differently. There has just been a fadeout into #7, which starts off abruptly with very vertical eighths in both flute and piano – a new character entering the scene. The staccato helps to emphasize the disjunct quality of the line. Two bars later, where the staccato has been omitted, Copland asks for ff vigorous 16ths. While the figure at #7 was static and a bit grotesque, now there is a scale passage with direction and forward energy that is imitated in the piano as well. It makes sense to connect the notes more at this point.

Between #8 and 10, there are brief articulation changes that represent character switches and should be adhered to. Heading into #9 after a lyrical section played with charm, Copland returns for a moment to the marcato character of #7. After this interruption of only three bars, he returns to the lyrical style with an instruction of soave. Notice how Copland’s staccato-legato marks evolve into simply staccato three bars before #10, a subtle but clear sign that he wants more energy approaching #10. Whether or not you imagine actual scenes with a cast of characters, it is crucial to absorb each of these subtle markings and realize them in sound and articulation changes that make the section come alive.

Movement Two

The second movement’s two musical ideas come from an earlier period, as do those for the outer movements. These ideas refer to Copland’s earlier nontonal writing, and from his Piano Quintet of 1950 in particular. Mood and sonorities are starker than in movements one and three, indeed somewhat mournful as the composer writes. Copland’s score details are once again important to help interpret the sparse beginning. The slow tempo and static backdrop of the piano make it difficult to shape the opening melody and maintain the stillness of the scene. Copland urges us to be freely expressive at the outset, and I try to take him at his word in order to move through the phrases; like the opening recitative of movement one, this is another place to try ignoring bar lines and meter. I also find it effective to use a thin sound with no vibrato. At the second bar of #1, where he asks for a warmer tone, putting the vibrato back in highlights the change. He also makes that designation at #8.

Decisions about tone colors throughout the movement are aided by Copland’s frequent expressive suggestions. According to Copland’s comments on the writing of Duo, he wanted to ask for a “thin tone” at a particular spot in the second movement. At the time, the commissioning flutists evidently warned Copland against ever suggesting that a flutist play with a thin tone! He responded by inserting harmonics after #3. I have used alternate fingerings for the E and C sharp rather than true harmonics, which for me work better to achieve the cold, still moment I hear there. This was a decision I made before hearing the “thin tone” story, and I pass it on as encouragement to listen with open ears and minds in this movement. It is the most difficult of the three to sell and I think benefits from some artistic daring to bring it off.

Movement Three

Movement three uses primarily short, accented articulations, with the important exception of the legato figure at #2 (and later at #13) discussed earlier. The effect of this section is that of holding the reins in briefly before letting the horses out at full speed again. The emotional control creates an interesting tension between high energy and the strain of pulling back just a little from it, as though going against gravity.

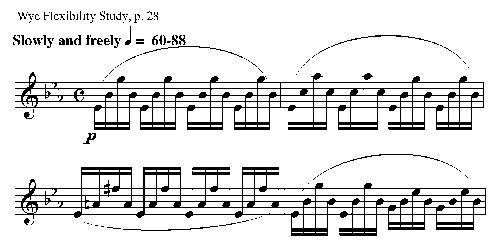

There are many articulation studies that help strengthen the tongue and coordinate it with the fingers. It is helpful to review basic concepts of single and double tonguing with Trevor Wye’s Practice Book on Articulation, volume 3 page 10 and onward, if you are having trouble with tone and articulation clarity. (See also Muczynski article, Flute Talk, October, 2008.) Melodic Studies 15 and 16 in Moyse’s 24 Little Melodic Studies are also good for double tonguing in the low and middle registers.

An etude collection that is not well known but quite excellent for intermediate to advanced players is Anne McGinty’s 20 Etudes for Flute. The etudes are contemporary in ideas and harmonies and provide a musical connection to what students today are playing and hearing. The first etude is on double tonguing with a jaunty, Copland-like motive that works on scalar and interval combinations. I highly recommend this collection for its effectiveness, as well as its musically modern and satisfying compositions.

As with the first movement, take Copland’s tempo and verbal indications seriously here. Though optimistically tonal overall and arriving up a half step to a triumphant E-flat major at the end, the movement’s middle section from #5 to #12 jumps into some of the atonal territory of the second movement, in an exaggerated and pointed articulation of disjunct intervals. The flute and piano banter back and forth, and there is an almost comic tone to this bizarre conversation, particularly if you exaggerate the accented notes as Copland directs. Give the tiniest bit of length to the notes with accent plus tenuto marks.

At #8 the instructions are more relaxed, and my own preference is to play this passage with longer note lengths, before returning at #9 to the pointillistic style. Again, noting the score’s details helps me understand and play this middle section more effectively than if I barreled though it all loud, hard, and short – as it looks to be at first glance.

Despite Copland’s mixed feelings about the Duo, some 35 years later, we are grateful for this fascinating compendium of Copland’s popular and starker nontonal styles. While many can play the work, it is still a challenge at the highest level of artistry.